Scientists at Univ. of Michigan Marvel at the Nanoscale Precision of a Natural Pearl

A University of Michigan-led team of scientists have uncovered for the first time how mollusks build ultra-durable natural pearls with a level of symmetry that outstrips everything else in the natural world.

“We humans, with all our access to technology, can’t make something with a nanoscale architecture as intricate as a pearl,” said Robert Hovden, U-M assistant professor of materials science and engineering. “So we can learn a lot by studying how pearls go from disordered nothingness to this remarkably symmetrical structure.”

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study found that a pearl’s symmetry becomes more and more precise as it builds, answering centuries-old questions about how the disorder at its center becomes a sort of perfection.

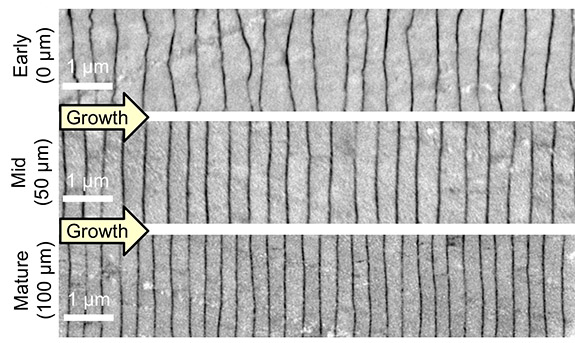

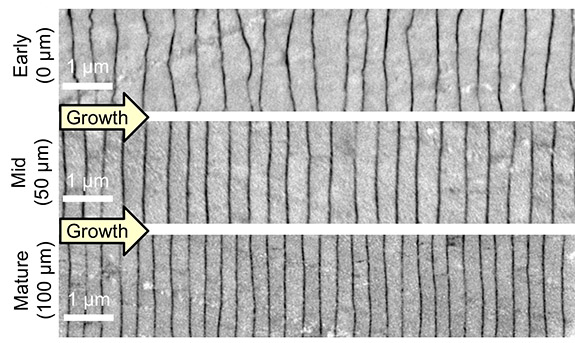

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that mollusks maintain the symmetry of their pearls by adjusting the thickness of each layer of nacre. If one layer is thicker, the next tends to be thinner, and vice versa. The pearl pictured in the study contains 2,615 finely matched layers of nacre, deposited over 548 days.

The layers, which make up more than 90% of a natural pearl’s volume, become progressively thinner and more closely matched as they build outward from the center.

“These thin, smooth layers of nacre look a little like bed sheets, with organic matter in between,” Hovden said. “There’s interaction between each layer, and we hypothesize that that interaction is what enables the system to correct as it goes along.”

The atomic-level nacre analysis was conducted in collaboration with researchers at the Australian National University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Western Norway University and Cornell University.

The team gathered their observations by studying Akoya “keshi” pearls, produced by the Pinctada imbricata fucata oyster near the Eastern shoreline of Australia. They selected these particular pearls, which measure around 50 millimeters in diameter, because they form naturally, as opposed to cultured pearls, which have a shell bead center. Each pearl was cut with a diamond wire saw into sections measuring three to five millimeters in diameter, then polished and examined under an electron microscope.

Credits: Image of nacre layers courtesy of University of Michigan; Image of pearls by UWAKOYA, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.

“We humans, with all our access to technology, can’t make something with a nanoscale architecture as intricate as a pearl,” said Robert Hovden, U-M assistant professor of materials science and engineering. “So we can learn a lot by studying how pearls go from disordered nothingness to this remarkably symmetrical structure.”

Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study found that a pearl’s symmetry becomes more and more precise as it builds, answering centuries-old questions about how the disorder at its center becomes a sort of perfection.

Perhaps the most surprising finding is that mollusks maintain the symmetry of their pearls by adjusting the thickness of each layer of nacre. If one layer is thicker, the next tends to be thinner, and vice versa. The pearl pictured in the study contains 2,615 finely matched layers of nacre, deposited over 548 days.

The layers, which make up more than 90% of a natural pearl’s volume, become progressively thinner and more closely matched as they build outward from the center.

“These thin, smooth layers of nacre look a little like bed sheets, with organic matter in between,” Hovden said. “There’s interaction between each layer, and we hypothesize that that interaction is what enables the system to correct as it goes along.”

The atomic-level nacre analysis was conducted in collaboration with researchers at the Australian National University, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Western Norway University and Cornell University.

The team gathered their observations by studying Akoya “keshi” pearls, produced by the Pinctada imbricata fucata oyster near the Eastern shoreline of Australia. They selected these particular pearls, which measure around 50 millimeters in diameter, because they form naturally, as opposed to cultured pearls, which have a shell bead center. Each pearl was cut with a diamond wire saw into sections measuring three to five millimeters in diameter, then polished and examined under an electron microscope.

Credits: Image of nacre layers courtesy of University of Michigan; Image of pearls by UWAKOYA, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons.